Sigmund Freud: Totem and Taboo; Totem Sacrifice as a Contract for Peace Inherited Through the Collective Psychic Realm (of Myth) - altereffekt.

The similarities between mythical narratives found in remote areas of the world have puzzled many researchers, and as such, have been troubling them in their quest to define the reasons for their resemblance, as well as the source of these stories and their structures. Many of the signs point to a unitary source of universal motifs found in different cultures in the world which appear common, making many researchers doubt about the existence of some form of universal mythical reality able to occasionally resurface and penetrate into different cultural narratives. One of those researchers is the early 20th century renowned psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, whose remarkable ideas have shaped the path and structure of future research, not only limited to psychoanalysis, but other related subjects, such as religion, mythology, anthropology, semiotics, etc. Among other outcomes, his outlook on some of the psychic phenomena occurrences found in his patients gave unique – and at times even described as fantastic – perspectives to the theory related to mythic essence and the symbolic representations found in it.

This paper attempts to summarize the main ideas of Sigmund Freud’s theory regarding the occurrence, evolution and reinvention of the totemic sacrificial concept as portrayed in the last four chapters of his “Totem and Taboo” inquiry, and try to offer a genuine interpretation regarding its possible relation to the later traditions linked to or emerging from it. Additionally, it suggests a perspective of the book’s relation to myth, the ‘mythical source’, as well as gives comparative propositions from different takes on myth and its preconceptions.

The Return of Totemism in Childhood

Freud begins constructing his stance in addressing the widespread phenomena of the ancient ritual of sacrifice and the sacrificial meal ceremony by taking as a base William Robertson Smith’s (1889) publication “Religion of the Semites”, embarking, thus, on a journey to trace its origin, evolution and meaning. In doing so, he points to the animal sacrifice as the oldest form of sacrificial meal, through which he is tracing the roots of the totemic belief systems, and further on attempts to develop a theory on its meaning, origin and later transformations.

Interpreting Smith’s conclusions, Freud accentuates as a prominent characteristic of the totemic sacrifice to be its covenant feast character, which serves as a unifying ceremony of a joint meal, where the kinship relations are reassured through participation in the sacrifice by sharing the totem meal between all the participants. The totem animal is therefore a unifying subject-deity, which brings the community in a joint ceremony to reassure the bonds and to claim their participation in the group. To enforce this argument he points to the detail noted in Smith’s studies that ‘savages’ usually eat in solitude and the only occasion where the food is shared and a joint meal takes place is during these sacrificial ceremonies. From this observation, he concludes that the totemic meal represents a celebration of the bond, not only between the participants, but an adhesion with deity itself as well, suggesting its existence being manifested prior to the emergence of any form of religion.

As an important shift in the development of the ritual of animal sacrifice, he further observes the evolution of the human cultures into agricultural ones and denotes the domestication of animals as fatal to totemism. Instead, the form of sacrifice is often substituted with vegetables, liquids or other forms of sacrificial offerings. However, as an intermediate substitute to this cultural transformation, he points to the wild animal – otherwise forbidden to be consumed – that takes the place of the previous animal that was domesticated, so that the ritual could proceed with newly introduced totemic figures. Thus, the ceremony, which confirms the bond and communality with one another and with the deity itself, finds a way to survive and evolve further on.

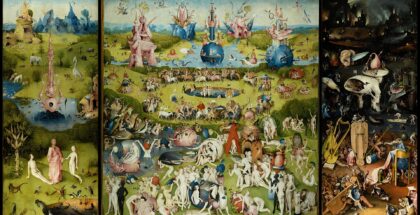

Freud goes on analyzing the nature of the totemic sacrifice festivals, noting the ambivalent emotional tendencies of both joy and remorse in its content. He draws a parallel between these tendencies and what he recognizes as “the Father-complex” found in children during his professional observations, concluding that the totemic figure in primordial cultures represents and acts as a substitute for the father. In supporting this claim he consults Darwin’s theory of the primal horde and suggests a possible situation – to which point the later traumas widely dispersed and developed in the general human psyche – where the sons of the primal horde due to being deprived from the women of the tribe and out of jealousy are tempted in committing a joint crime of eliminating the superior father who keeps all the women for himself. A crime for which they subsequently repented, either naturally, or, as Freud suggested, out of the new chaotic situation emerging from the father’s disposal and absence, who constituted the governing head of the organization maintaining the hierarchy of the clan. As a consequence of these events, in the following generations the psychic state of remorse and satisfaction develops further and is later transformed into the first taboos of totemism – Murder and Incest. The remorse and inability to establish new power relations – as none of the brothers had the power or ability required to maintain the hierarchy – created the necessity to avoid heterosexual relationships inside the clan and, thus, establishing for the first time the tradition of exogamy in human societal existence. Freud emphasizes that in order for the clan to survive, this step must have been of crucial importance and necessary. However, after being eliminated, the longing for the father and for the order that only he could maintain urged the sons to yearn for the old days and acknowledge his supreme role. These developments enabled the totem to become the best substitute for the dispossessed father, for whom now the feeling of admiration was venerated by a sacrificial feast, which also contained an expression of joy in getting rid of him. Through the totem, the brothers found a covenant with the eliminated father, and thus gave birth to what would consequently become a sacrificing ceremony and later evolve into the archetype or a religion model. In other words, the repentance found an intermediary form of commemoration that brought them peace, both inside themselves and in between. As such, the prohibition of killing the totem, except in the joint feast, meant a repentance for the first act (the killing of the father), but which in itself also contained the fear of subsequent fratricide, and that later evolved in the prohibition on all killings, as it further developed into the general norm of Thou shalt do no murder. Here, Freud suggests a transformation and a basis for the totem sacrifice in becoming a social contract for maintaining peace and order in the system, as well as to serve as a veneration for the father and the ceremony of expressing remorse. Thus, for both totemism and exogamy, Freud points to a common origin in the first crime, which for him was a rebellion of the sons against the patriarchal order, but which inevitably helped establish the patriarchal foundations of the society.

From Totemism to Religion

In getting back to the idea that later religions trace their emergence from totemism, Freud suggests two main threads he could detect in proving so: (1) the theme of the totemic sacrifice and (2) the son–father relation. Through these two threads, the source which in itself bears the content of sacrifice, as well as the ambivalent emotional attitude of the primordial binary opposition, in return gave birth to a new belief system in which the figure of the disposed-of father was exalted in the place of a surrogate God-deity. The patriarchal rule was once again firmly established out of remorse and out of the fear of chaos, but this time with the absent father figure represented through surrogate totemic personifications. Thus, for Freud, the scene of father’s “greatest defeat” becomes the substance for his “greatest triumph”, pointing to the emergence of Kings as consequence of these developments where the patriarchy found a secure ground in the temporal return of the father rule in different governing forms.

Since the idea of God has emerged “from some unknown source”, the sacrificial meal had to adapt and reinvent itself with the new system. This idea of God, which now comes as a central figure, is represented twice, once as a God and once as the totemic animal victim. However, Freud suggests that the origin of the idea of God is to be traced exclusively in the totem.

In seeking to explain the development of later forms of religions, Freud suggests that the two driving factors behind it are always represented in the dichotomy of (1) the sons’ guilt and remorse; and (2) their rebelliousness, which again would point to the ambivalent emotional relationship, a characteristic of the Oedipus (parental) complex. Almost expectedly, in the further development of this dichotomy of relations, Freud notes the appearance of Christianity as a peak culmination of the Son’s remorse by sacrificing himself for the primal deed. But in doing so he did not only compensate for the initial crime, but also substituted the Father in the central deity figure. In a way, through self-sacrifice the sons’ reclaimed the throne, and thus, a son-religion replaced the father one. Building this argument, he further relates to the story of the Hero and the Chorus, a tragedy which in itself contains both sacrifice and exaltation. Coinciding with Blumenberg’s (1985) notes in the ability of myth to infiltrate later narratives and fill its gaps, he supposes that the existence of these philosophical ideas in some form were able to infiltrate the new “myth” of Christian passion. In addition, the introduction of saints in later developments is contextually paralleled to Roman deities (Blumenberg, 1985).

Before concluding, Freud reaffirms with the ‘brave’ remarks that the religion as a later form of belief system has its roots in the Oedipus (paternal) complex and is merely a reshaping of this initial event, hence its over-dispersion around different beliefs systems and religions.

The Nature of the First Crime

Finally, Freud restates and establishes the idea behind his theory, which to be understood, has to primarily be acknowledged as a psychoanalytic interpretation, having in mind that the conceptualizations which he provides are generally of psychic character, and the inherited knowledge and information need to be seen only through this aspect. As affirming in the later remarks, the perception of the idea and the narrated story needs to be asserted from the perspective of dealing with a ‘collective psychic reality’ able to affect societies just as mental processes affect and occur in the individual. He calls it a collective mind, that clearly is in accordance with the phenomena which his counterpart, Jung (1949) terms as collective subconsciousness in his observations of the ‘Child archetype’ symbolism in dreams.

For further clarification, Freud, as if trying to avoid appearing overly superstitious, employs more scientific tones in describing the heritage of this knowledge from generation to generation as something natural and evident, raising two further questions: (1) how much can we ascribe to psychical inheritance in generational sequence? and (2) what are the mechanical operations employed by one generation in order to convey the mental state to the next one? He suggests that these issues seem to be addressed through the inheritance of psychical disposition which in order to be crystallized in the life of the individual, authentic effort needs to be added.

Freud clarifies that in order to understand the past collective events and the occurring phenomena in the individual psyches of neurotics, an unconscious deconstruction of mythical material needs to proceed so that we could extract the true message out of them. He points to the characteristics of neurotics and the appearance of the sense of guilt and remorse concerning deeds they did not commit, but rather experienced as a feeling or thought in the psychic and emotional plane of existence. Suggesting that in them, the thought is equal to factual reality, and that they give primacy to the former. He takes this example as the closest example that resembles the psychic reality of the primordial man. This grey zone between reality and the psychic realm – for both primitive man and neurotics – leads him to the need to clear the last doubt before concluding: did the first crime of the horde brothers really took place or was it just an impulse felt by them, which could not be realised, but nevertheless in the collective mind of the succeeding generations it is impulsively realized and experienced as true.

Freud concludes with the comparison between the primitive man and the neurotic cases and how they experience psychic realities and factual realities, in stating that for neurotics it is the thought that matters and on the other hand, for the primitive man the thought is immediately transformed into action. By this, he suggests as an indisputable outcome the fact that the ambivalent feeling of the sons was in fact completed into action and that the initial deed actually took place. This means that the first crime did happen and it was not merely an impulse.

Turns out that the sacrificial act, then, is a central part in this narrative, although only serving in supporting his main argument – the existence of Oedipus complex which escalated in the first crime and was subsequently inherited as a collective psychic trauma, in what Freud names as the human collective mind.

Semantics of Sacrifice

Sacrificial meal is undoubtedly a widely spread phenomena which even to this day – when human “primate” communities rarely exist in their original cultural settings – is able to survive in different cultures and traditions. What seems to be important out of Freud’s impressions and conceptual conclusions is the possibility to use them for better understanding the ‘everliving’ ritual of sacrificial meal, the realities of the (mythical) stories and symbolisms resurfacing and reinventing themselves in different cultures, epochs and areas of the inhabited globe.

In deconstructing mythical narratives, Detienne (2014) seeks to establish cultural conjugation between two mythical stories in deciphering the meaning of the “The Myth of ‘Honeyed Orpheus’”. Freud, instead, chooses to only move on the combating dichotomy in the Father-Son relationship and the inner dualism of son’s driving motivations: repentance and rebelliousness. While he does seek and take many similar culture-specific (Wolpers, 1995) relevant ‘thematics’ and motifs between stories in trying to establish a relation and decipher the meanings out of different occurrences, he seems to dismiss a major event in the father-son narrative: the son sacrifice of “Abraham the Patriarch”.

Noting the twist in the narrative with the emergence of the son-religion, the Abrahamic story of ‘son sacrifice’ has a lot to add to the central oppositional forces and could fit well as a final payback from the father, with a third non-material deity intervening in resolving the quest by substituting the son for a ram/lamb and thus taking the burden off from both sides. I could only speculate that it is the appearance of an independent non-material god, able to stand above the father-son dichotomy, that which prevented Freud from engaging this story to the narrative/plot.

Throughout Abrahamic religions, the son-sacrifice “myth” is a central story of sacrifice offering in affirming one’s belief in a supreme deity, while the reward – the substitute for the son – becomes central to the following practices in the ritual of ‘Sacrificial Feast”, which is for instance actively observed in Islamic tradition to this day. The tradition of animal sacrifice is, therefore, explicitly changed from one of totemism to an intermediary method to ascertain one’s belief to the third intermediary – and rather governing side – the God. Additionally, Jesus is characterized as the ‘lamb of god’, who, as suggested by Freud, effectively fits in the narrative of offering himself as a sacrifice, and so in taking the primacy from the father.

Possibly, the Abrahamic religious traditions could offer more perspectives on this revenge and on Freud’s theory with the “paternal complex”. One such case would be another detail that could be emphasized, the study on the fratricide instead of patricide, in which Cain kills Abel, and thus could further complicate the father-sons dichotomy in deconstructing collective subconscious realities and related myths and beliefs as its byproducts. Leaving out these important plot-twists in the narrative which Freud builds up in supporting his claim of the “Father complex” is puzzling and opens the door for doubts if it was intentional having in mind that the ‘third intermediary’ constitutes a breach to the father-son dichotomy and doesn’t serve well the typical dual, opposition built narrative.

Another peculiar and rather esoteric insight – with the new perspective it offers – on the process of offering animal sacrifice to deities is found in Gurdjieff’s (1950) “Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson”. In chapter 43 of the Third Book, “Beelzebub’s Opinion of War”, Gurdjieff takes a different turn on the animal sacrifice, and in constructing his story he provides it as an alternative to human deaths (as a consequence of wars) and the vibrations released in these processes, which Earth requires in keeping its planetary, vibrational and interplanetary cosmic balance due to specific energies which are released from the living beings also found in the process of death. This process, he suggests, is either achieved by conscious spiritual labor and intentional suffering, or through the process of death. In the story, the wise people of the time discover that this energy, is also released to some extent by animals and if they would seasonally sacrifice animals and bring back the old tradition of animal sacrifice to deities, the way for nature to fulfill this need will not be realized through wars and destruction and the world could see peace and less human sufferings. So again, the offering of animal sacrifice to deities is proposed as a solution and a form of contract for peace between men in order to avoid destruction and chaos (Gurdjieff, 1950). Although this theory is extracted from a novel, having in mind Gurdjieff’s (1963) successive autobiographical publication “Meetings with Remarkable Men”, also part of the “All and Everything” trilogy set, it is relevant to mention that the source of his theories – from which the stories in the novel are built – contain wisdom and knowledge gathered from his ethnographic experiences and travels among different esoteric communities in Central Asia and the Middle East. This remark does not seem much different from what Freud suggests, and perhaps because his topic is fictional it might sound fantastic, nevertheless looking from today’s perspective it would not be more improbable than Freud’s theory of the primal horde.

Concluding remarks

Getting back to Freud, what appears as an apparent suggestion out of his take is the sacrificial feature acting as a central part in the establishment of a new order or a peace inside the dispossessed community. It offers both a societal order and peace on the one hand, and on the other a perceived forgiveness and repentance in the collective psychic realm, which is able to parallelly exist with the individual human consciousness. Freud emphasizes his inability to confirm the ways of how this information is transmitted between generations, but he clearly states the fact that this informational baggage exists and affects the individual and collective psyche alike. In line with Barthes’ (1957/1972) observations, Freud is satisfied with and interested only in the reduced and simplified core significations of the mythical substance.

This commonly acknowledged reality by Freud, also present in many other authors, such as Donald (2001), Jung (1949), Shore (2014), etc. that the human individual is not independent of the inherited amount of knowledge and information which is autonomously passed generation by generation, determines important functions in one’s existence. This innate knowledge is the “collective psychic reality” that Freud calls the “collective mind”, which itself is the container of the information and experiences in all of the human evolution. As Jung (1949) suggests that it inhabits and resurfaces in individuals in the dream state through general symbolisms and imagery, we can clearly understand that this ‘parallel realm’, or ‘psychic reality’, is not necessarily limited to dreams, but rather it is able to frequently reappear and reinvent its story in different human activities, such as myth, religion, tales and other related narratives (Jung, 1949). This fact is of crucial importance in understanding the ‘mythical reality’ or the source of the myth which exists and evolves in what Donald (2001, as cited in Jensen, 2014) calls the ‘hybrid mind’ as a result of the synergies of many brains.

In this journey of Freud – which is of great interest to the study of Myth – there is a possibility to conclude in two main points: (1) first, the idea that the ceremonial sacrifice is functioning as the base for communal reassurance, and as such poses as a contract for societal peace, which in the case of the primal horde meant a peace out of repentance and fear; and (2) to reaffirm the existence of a ‘collective psychic reality’ from which most of the dream world – and thus the mythical stories – take their content from, and that they are more closely related to this impersonal universal human nature rather than being individual creations or overly culture-specific motifs (Wolpers, 1995). Hardly any culture is able to escape the universal symbolism and the knowledge it produces, and as such myths do resemble the joint human natural attributes and joint primordial past, be they outsourced from the physical reflections or from inherited collective psychic traumas revealing themselves in the form of dreams, myths, tales or other creative expressions. Even in the mytheme syntagmatic structure, the narrative of myths – as partly documented in Levi-Strauss (1955) studies – resemble each other in various areas in the world, especially noting that translation has no direct effect on its structure. It is important that we draw the conclusion of the mythical reality of the subconsciousness, as it fills an important gap in the understanding of myth and its function in human understanding of cultures and the nature of human collectivity in general. Although it has been regularly suggested, it could never reach a certain recognition as a fundamental part in the existence of myth and related products in the broad connotative meaning of the term.

Myth is able to maintain itself and reappear. Myth is more adaptable than any religion or tradition and itself contains the genuine realizations and beliefs of a culture and is able to infiltrate any invention — forcefully or not — on the culture. As such, it is able to penetrate any newly emerging or outlived tradition. Thus, Myth exists independently of human effort to maintain it and in parallel with human societal evolution, it introduces the culture to the individual from outside-in and yet it comes to life and is manifested from the inside-out. (Shore, 2014)

Indeed, in the effort to decode the process of the inheritance of the information, Freud is right to suggest Goethe’s Faust verses “What thou hast inherited from thy fathers, acquire it to make it thine”, because we are able through it to semantically understand that the inherited information needs to be reasserted and materialized in order to be realized a new, and thus be able to understand the terra intermedia (Jung, 1949) and myth as its inhabitant.

Bibliographical references

Detienne, M. (1986). The myth of “Honeyed Orpheus”. In Myths and Mythologies: A Reader. (pp. 276-289).

Donald, M. (2001). A mind so rare: The evolution of human consciousness. New York: Norton & Company.

Freud, Sigmund: “The Return of Totemism in Childhood”. Totem and Taboo [1913], trans. James Strachey, Routledge, 2001, pp. 154-187.

Freud, Sigmund: The Interpretation of Dreams [1899]. trans. James STRACHEY, Basic Books, 2010, Chapter 5, pp. 278-283.

Gurdjieff, G. (1950). Beelzebub’s Opinion of War. In Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (pp. 245-308). New York: E.P. Sutton

Gurdjieff, G. I. (1969). Meetings with Remarkable Men [1963]. Eastford, CT: Martino Fine.

Jensen, J. S. (2014). Introduction to Part V: Cognitivist Approaches. In Myths and mythologies: A reader (pp. 323-336). London: Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1949). The psychology of the child archetype. The archetypes and the collective unconscious, 9 (Part 1), 97-119.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1955). The Structural Analysis of Myth. The Journal of American Folklore, (68), 428-444.

Shore, B. (2014). Dreamtime Learning, Inside-Out: the Narrative of the Wawilak Sisters. Myths and Mythologies: A Reader, (pp. 358-389).

Wolpers, T. (1995). Recognizing and classifying literary motifs. Introduction. In Thematics Reconsidered, (pp. 4–11).

*Marrja e përmbajtjeve të plota apo pjesore të artikujve lejohet vetëm me shtimin e referencës për postimin origjinal në blog.