Painterly Transmediality in Intermedial and Itersemiotic Space – Victory over the Sun: The World’s First Futurist Opera - altereffekt.

Taulant Salihi | Më 23, Jun 2021

I am delighted to share my first article featured in a printed publication in the debut series of ‘Intersemiotics & Cultural Transfer,’ a collaboration of the ICT Research Group – Budapest and the Transmedia Research Group – Tartu, edited by Katalin Kroó and Kata Juracsek, with contributions from Maarja Ojamaa, and a renowned consulting board from the fields of semiotics, literary-, media-, and translation studies, including figures such as Peter Torop, Ágnes Pethő, Marko Juvan, among others.

In my article, “Painterly Transmediality in Intermedial and Intersemiotic Space” I highlight the transmedia transfer and adaptation of the painterly identity and narrativity into the intermedial and intersemiotic space of the “Victory over the Sun” opera stage.

I am grateful for the opportunity to be featured in this series and to have also contributed by designing the cover for the introductory publication. Here’s to many more editions!

Abstract:

In this paper, I observe the intermedial and intersemiotic space of the Futurist opera performance Victory over the Sun (Победа над Cолнцем). This is a two-act joint work of Aleksey Kruchenykh (libretto), Mikhail Matyushin (score), Kazimir Malevich (costumes and set design), and includes Velimir Khlebnikov (prologue) and Vladimir Mayakovsky with the prequel performance in which I detect a painterly transmediality performed on the stage. The task is handled by consulting seminal semiotic and media text, and also by shedding light on the conceptual, stylistic, and aesthetic eccentricities of Kazimir Malevich and the importance that this moment had on his artistic oeuvre.

Read the full final version of the article at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375546970_Painterly_Transmediality_in_Intermedial_and_Itersemiotic_Space_-_Victory_over_the_Sun_The_World’s_First_Futurist_Opera_2023

June 2021 Draft Version:

“All is well that begins well and has no end…”. I would like to start this paper with a quotation from the final part of the opera, acknowledging the limitless possibilities of outcomes from the interpretations of this excessively avangardist “open work” of the past century.

This (journey) is an attempt to examine the intersemiotic space of the revolutionary and conceptually radical futurist opera Victory over the Sun (1913). Although other futurist operas were taking place around the same period of time (ex. Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “A Tragedy” played a day earlier and was considered as a prequel to it), headlined as “The World’s First Futurist Opera”, with its uniqueness and radical concept, it indisputably constitutes one of the first – if not the first – of its kind performances. The paper focuses on observing the transmedial potential of the painterly segments found in the integrated intersemiotic production of the experimental opera performance, materialized through the costumes and set design, which in the case of this performance is the contribution of Kazimir Malevich, coinciding with the conceptual turn in his oeuvre, theory of painting and artistic practice, from ‘Cubo-Futurism’ to Suprematism – the concept of pure abstract non-objectivity in art.

A radical cultural turn for the modern future: The First Futurist Opera

Victory over the Sun, created in a joint effort by the futurists Aleksei Kruchenykh (in charge of the libretto), Kazimir Malevich (set and costumes design), Mikhail Matyushin (composer), together with Vladimir Mayakovsky (with the prequel performance) and Velimir Khlebnikov (prologue), is considered to be the most influential of multiple Russian Futurist operas at the beginning of the 20th century. With its revolutionary and extremely nonconventional content, it exercised a major impact on other artists who acknowledged this new irregular and radical narratorial approach as an attractive stylistic ideology for creating artistic products. Being a complex artistic project, combining different artistic practices and methods, it was founded on new and rather radical ways of thinking, in terms of fine arts, as well as other artistic and cultural forms of expressions. As such, it constitutes one of the central Futurist creations, representing a dynamic conceptual shift in ideas, which were fundamentally tied in the beliefs and motifs of rejecting the old in favor of a modernist technological future, implying a new sense of the ‘spiritual’, while also positioning itself in leading the revolutionary philosophical ideas of an advanced human future in contrast to the old social norms and morals.

According to some historical reports (Bartlett, 2012; Gurianova, 2012) the opera premiered at the Luna Park Theater in St. Petersburg, either on 3rd or 5th of December 1913 and by being immensely ahead of its time (in its ideas), some studies suggest that it wasn’t well received by the wide public, but applauded by the few avangardista followers (Ostashevsky, 2014). This According to some historical reports (Bartlett, 2012; Gurianova, 2012) the opera premiered at the Luna Park Theater in St. Petersburg, either on 3rd or 5th of December 1913, and by being immensely ahead of its time (in its ideas and construction), reports suggest that it wasn’t well received by the wide public, but applauded by the few avangardista enthusiasts (Ostashevsky, 2014). This was perhaps meant to be the fate of such Futurist ‘provocation’, however, in the ‘metaspace’ of historical events, in particular those central to the artistic and cultural paradigms, it represents a courageous step towards the modern future, embracing the world of technological innovations as the epitome of humanity’s victory over nature and its laws of constraint – in the opera gravity and death are seen as nature’s agents, the antagonists. A nature personified in the old conventional world that the artist with the advent of new technological discoveries could not justify anymore.

To technically transmit these unconventional ideas, the opera included different artistic mediums, methods and practices. In line with libretto’s anti-discursive narrative (or anti-narrative), the experimental Zaum language integrated in parts of the script, the visual Cubo-futurist abstraction (conveyed in spatiotemporal/kinetic modality), and the atonality, irregularity and dissonance of the musical composition (which due to the shortage in funds was solely performed by a piano), the opera represented an integrated intersemiotic (scenic) ‘performative’ concept, where each unit is aiding the others, and at the same time travelling freely in the intermedial space, revealing their transmedial potential.

By being a short play and featuring only two brief acts with an all-male cast (the Stas Namin Theater reconstruction introduces female actors, Figure 3), it doesn’t provide an easily detectable plot, except the one driven by the main course of the topic “the capture of the Sun by the Strong Men of the future”. It points to the evident dominant motif of embracing the technology-driven human future and modernization, in contrast to the conventional morality of the old norms. Through its omnipresent anti-rationality and anti-discursivity (expressed in different semiotic systems), it could unmistakably be referred to as an anti-opera, provoking a critical review on the general conventionalities of culture. Remarks portraying it as a reflection of the socio-political realities of the early 20th century Russia and Europe would not be mistaken too, as does Eugene Ostashevsky (2014) with his reflection in politically categorizing it as an anti-bourgeois artistic work/protest.

What the opera offers through its intersemiotic combination is the totality of anti-discourse, through all its units, forming a temporal semiosphere micro-model on stage; with the script/text, visuals, physical performance (act/gestural/dance) and music. Through these channels, it aims to destroy the old built norms and established codes, making way for a new reason and perspective of looking at the world and arts. Motifs of radical change and negation of the established conformism follow in all possible forms of signification. The universal symbolism of the Sun as a light, reasoning, and the ultimate goodness, here is downplayed in an antagonistic order by the act of capturing it, while the phenomena of time traveling on the other hand, which seems to be suggestive of the technological developments witnessed during that time by the creators, is shaped as the new protagonism. The technological advancements are preferred instead of the outdated symbolic notions of the Sun and light, radically exposed as the agent of antagonism representing the old (artistic) world values. The futurists were aiming for a strong countercultural stance by questioning universally established norms, beliefs and knowledge (Larionov & Goncharova, 1913). In the opera, time stops. The new time (count) is linear. Everything seems to be restructured and the sun of the old world of nature is captured … and so, death, as the ultimate human (-condition) mystery, is canceled!

Painterly transmediality in the intersemiotic and intermedial space

Theatrical performances in essence, comprise a fully integrated intermedial production, be that classification based on qualitative interpretation, modalities or technicalities (Elleström, 2010). However, experienced from the recipient’s side (of the semiosis/sign production process), it constitutes a singular spatiotemporal audiovisual performance with a dominant visual component. By categorizing it in this order, we establish the understating for the main channel of mediation to be the visual one.

Transmediality, as a relatively new term for the phenomenon, has frequently been addressed through different conceptualizations in regard to its terminologically specific components, but the ones that would necessarily preserve, would constitute its denotative character of beyondness and freedom of media dependence in conveying the message/story. The material and qualitative components of intermedial phenomena have been examined and reviewed as well, and in such pre-existing notions it is essential to begin with the defining stance regarding the transmedial character as such. Transmediality can be understood as a narration phenomenon, or a narrative, that is able to float freely between media (Evans, 2011; Rajewsky, 2005). This free-float between media territories and transgression of media borders, be they of material character or a qualitative one is not restricted or exclusive, thus referring to its ability for a multiple parallel activity.

In this case, the study is concentrated in examining the painterly transmediality in the intersemiotic space of the opera performance. As such, it would also be necessary to clarify the notion of the used term painterly, which in this case refers to the two-dimensional pictorial/painting medium as we know it, including particular styles, such as definitions of abstract/non-representational coloring surfaces acting as the main subject of a painting. While the term keeps the exclusivity to the painting medium and its technicalities, here it is also used as a reference for both the technical-media origin and its conceptual implications. On the other hand, we consider the opera – like any other theatrical performance – as an intermedial and intersemiotic product, which as earlier mentioned, due to its vital dependence, is dominated by the visual unit, constituting a predominantly visually percepted medium.

Acknowledging that we are dealing with an intersemiotic space, where individual semiotic units retain the possibility to function both in a single unitary mode and separately at the same time, it abides to the well-known definition of the theatre as an intermedial platform with open possibilities for transmedial phenomena to take place (Elleström, 2010).

The image becomes performance – how the painterly idea adapts into a transmedial narrative

The main transmedial point is to transform the concept of the painting/painterly idea into a form of art performance within the opera. Although the visual domain dominates and helps framing the anti-discourse narrative of the libretto, the dissonance/atonality of the musical composition and the irregularity of the verbal sounds and dance acts (thus participating at the same time in the intermedial course of the performance), its painterly portion has the potential to use this space and media combination for leading a parallel narrative. Therefore, the first degree of transmediality takes place naturally due to the aforementioned dominant function of the visuality in the intersemiotic space of the opera, instantly suggesting a possible visual transmediality independent of the integrated work. Through its various micro-units and their free scenic movement, the theatrical performance offers an overall visual composition and independent conceptual story open for interpretation. In a deeper observance, we recognize the painterly transmedialia inside this visuality, where compositional order and stylistic painterly elements (of Cubo-futurist and Suprematist style) are evident and shape the visual perception. Colors, shapes, movement, all contribute to the transmission of the painterly conception of the scenic performance. This evokes the typical compositional narrative of the painterly media conception and ideas, adding to it the spatiotemporal modalities present in what would later be known as the performance art of the conceptual art paradigm.

The episode of painterly transmediality in this intersemiotic space also portrays the ability of the Futurist and – here planting the seed for – Suprematist painterly and cultural ideas of pure abstraction, non-representationality, disappearance of the natural forms and a new cultural thinking. It also points to the ability to transgress between media boundaries and freely circulate in the intersemiotic space of the scenic performance, taking different roles, while at the same time helping other sign systems to enhance their expressive joint intermedial performance. This painterly transmediality, in a performative combination, dominates and makes use of the dances, gestures and movements, using them for its painterly structural composition, in that way operating a separate independent visual and performance art narrative of its own.

From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism – from the radical to the beyond

It seems that from all the authors of this revolutionary futurist opera, Malevich ended up harvesting its fruits the most. By continuing on the lines of dynamic negation of the conventionalities of painting (and culture), at one point confirmed by a letter he wrote to Matyushin in 1915, when a second staging of the opera was proposed he realized what his earlier works were aiming for and were the representatives of. Understanding that what he was creating – and aiming towards – was the birth of a new purely non-objective art, referred to as new painterly realism, in the letter addressing the design of the curtain he explains that “…This drawing [or design] will have great significance for painting; what had been done unconsciously, is now bearing extraordinary fruit” (Letter of 27 May 1915, published 1976, p.156). As suggested by Malevich himself, in his breakthrough introductory essay of 1915, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism”, Futurism has completed its mission of fast-forward dynamism challenging the static objective form, and by doing so, its true followers by “spitting on it” have to transcend to the new formless beyond of Suprematism, where creation is absolutely new, non-objective and innovative. By framing it as a new painterly realism, he was indicating its strong character as the new state-to-be of arts and painting, retaining its links to the painterly character as point of reference for other cultural practices.

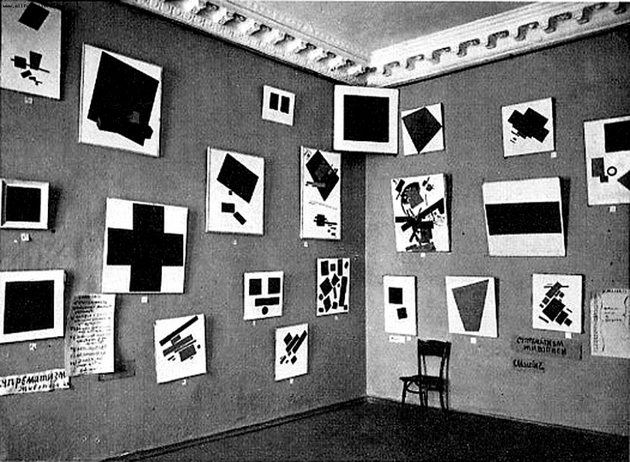

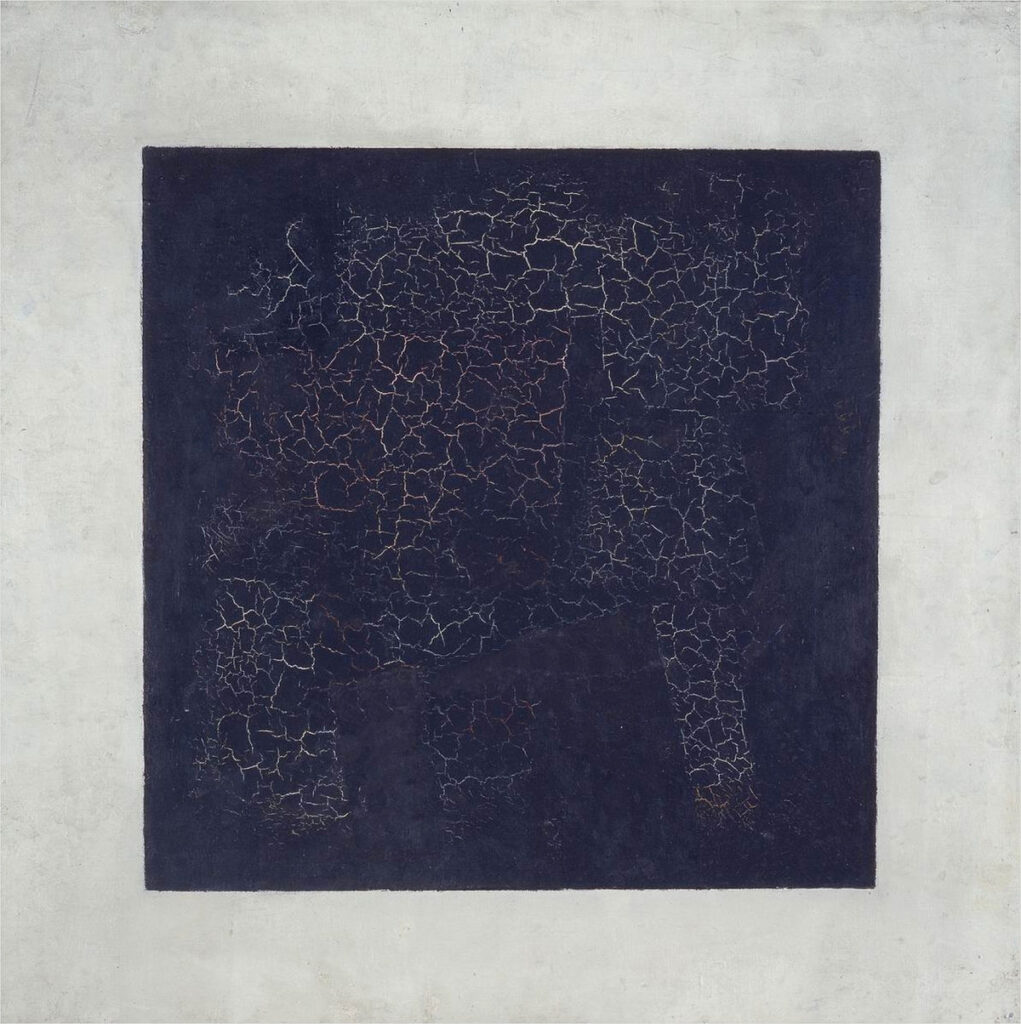

Taking as an example the concept of the positioning order of the artworks in the introductory exhibition of Suprematism, conceptually named as “The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10” (image below, Figure 3), the idea of radical non-objective abstraction is an evidence for how the logic of Malevich’s Suprematism operated in the early days. The supposed cross spot in a traditional Orthodox Christian home is substituted with the famous Black Square, while the cross imagery is positioned in the bottom left as if representing a different secondary dominion.

To add to it, Malevich’s death ceremonial included the Black Square instead of the cross, clearly indicating once again its relation to the non-objective representation of any visible conventional phenomena and what was central to the idea of Suprematism, that “anything imitating objective reality is the art of the savage, which Suprematists have now completely renounced” (Malevich, 1915).

It is this fundamental detail that distinguishes Futurism from Suprematism and which suggests for the latter to have transmedialy shaped the opera by independently (spatiotemporally) performing its idea. Futurist painting offered the reflection of movement in the visual painterly medium. Its preferred topics were cubist technological objects rather than natural landscapes. Suprematism exhausted the use of this technological dynamism in paintings and gave birth to the representation of pure subjectivity with no relation to objective reality. In the design set of the opera we see 3-dimensional geometrical shapes taking the form of the futurist characters; or the sun being represented as a black square, black circle, or as a wheel (Crane, 2013). Suprematism is not only participating/aiding as one of the units in the futurist anti-discursive narrative of the opera, rather it is fundamentally debuting its conceptual painterly idea of representing reality through pure subjectivity in the form of art performance (two levels of transmediality).

To reiterate, in intersemiotic (audiovisual) performances – this anti-opera being one – the dominant unit of signification – as in any other theatrical performances – remains the visual mediation. By examining what it adds, the intensity with which it does it, and the ability of the painterly elements in it to even act as transmedial referenta of the cultural idea behind the overall mediated narrative, we deconstruct the independent stories told through it. In 1916 Malevich outlined the importance of subjectivity in arts: In the forms of Suprematism, the new realism in painting, are already proof of the construction of forms from nothing, discovered by Intuitive Reason. It is this painterly (and cultural) idea, unconsciously inhabiting the visual space of the opera that could be accounted for a transmedial art performance, leading not only itself, but also the author in his quest for the meaning of purely subjective art. The inherent travelling attribute of transmedial content (Rajewsky, 2005) is centrally related to its performative act, through which it surpasses borders and adapts to new forms, as do the opera visuals with both the adaptation to the main narrative and its independent performance art activity.

We can now partly conclude that what was created unconsciously gave birth to a new concept of painterly idea, providing an example of the independent life of the artwork leading the artist. This type of ‘meta-transmediality’ acts as a leading-transmedial narrative, where the artwork leading the artist develops the subject of its own. Together with the possible art performance interpretation we witness the two available transmedial phenomena through the prism of visual art genre. Similar subconscious artwork-creation performance is known as action-painting, widely present in abstract expressionism – Jackson Pollock being one of the most notable practitioners – where the artist paints on the canvas without presupposed intention, surrendering to the feeling/action to lead him and the outcome instead.

As in most of the literary works, here too, the cultural backdrop is a powerful factor in the reading and interpretation of the artistic expressions. To fully grasp and understand the levels of visual (and painterly) transmediality and performance art inside the opera, requires a familiarity with the painterly and artistic ‘intertextualities’ involved. The anti-opera was a multidimensional artistic channel for new art forms to take place, giving birth to new ideas that will shape the future. When the interpretation is open, the transmedial potential is limitless, just as the futurist strongmen in the last part of the play conclude:”… the world will end but there is no end to us!”

Consulted sources:

Crane, A. (2011). “Malevich and the American Legacy” exhibition at Gagosian Gallery Madison Avenue, pt. 1, as filmed by GagosianGallery http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqmH-vwn6Tw&list=PLzrcuYhjOSHxIkac0sa5pbHy551dEsUcH

Eco, U. (1989). The open work. Harvard University Press.

Elleström L. (2010) The Modalities of Media: A Model for Understanding Intermedial Relations. In: Elleström L. (eds) Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230275201_2

Evans E (2011) Transmedia Television: Audiences, New Media and Daily Life. New York: Routledge.

Kruchenykh, A. Victory Over the Sun: The First Futurist Opera. Ed. Eugene Ostashevsky; tr. Larissa Shmailo. W. Sommerville, MA: Cervena Barva, 2014. III-XVII.

Larionov, M., & Goncharova, N. (2019). Rayonists and futurists: a manifesto (pp. 669-672). transcript-Verlag.

Matyushin, M. (1913). Victory Over the Sun. Score. as scanned in Bartlett, p. 70-86

Malevich, K. (1959). The Non-objective World (1924), trans. Howard Dearstyne.

Malevich, K. (1900). From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting (1915). Art in Theory, 2000.

Ojamaa, M., & Torop, P. (2015). Transmediality of cultural autocommunication. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(1), 61-78.

Rajewsky, I. O. (2005). Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: ALiterary Perspective on Intermediality. Intermédialités / Intermediality,(6),43–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005505ar

Seed, D. (1997). The Open Work in Theory and Practice. Reading Eco: An Anthology. Rocco Capozzi, ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Till, N. (2014). [Review of the book Victory over the Sun: The World’s First Futurist Opera ed. by Rosamund Bartlett, Sarah Dadswell]. Music and Letters 95(1), 116-119. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/545351.

Wolf, W. (2007). Description as a Transmedial Mode of Representation General Features and Possibilities of Realization in Painting, Fiction and Music. In Description in literature and other media (pp. ix-87). Brill Rodopi.

*Marrja e përmbajtjeve të plota apo pjesore të artikujve lejohet vetëm me shtimin e referencës për postimin origjinal në blog.